The first step in a long history of expansions.

In a world and time when the Famicom reigned supreme in Japan, developers were not satisfied with the ROM cartridge format and its limitations. Not only this, but many gamers were wanting additional features for their Famicom games, such as the ability to save data. These were just some of the reasons why the Famicom Disk System was released in Japan on February 21, 1986.

Not only did the Disk System provide gamers and developers with more flexibility, the disk format also provided a larger capacity and the ability to rewrite data directly to the disk. The Famicom Disk System plugged directly into the Famicom via a RAM adapter that plugged into the cartridge slot. The RAM adapter housed an additional 32KB of RAM for temporary program storage, 8KB of RAM for tile and sprite data storage, and an ASIC (Application Specific Integrated Circuit) called the 2C33 that controlled various aspects of the floppy drive and the hardware. The system also had a more advanced sound chip that gave the games a unique sound that could not be easily replicated on a cartridge based game. The system could be powered with the included AC adapter or six C batteries. The disks themselves were proprietary 2.8” “Quick Disks” manufactured by Mitsumi Electronics and had a capacity of 64KB per side. Many of the titles used both sides of the disk cards for storing game data. Initially, most of the disks were produced without dust covers in an attempt to cut manufacturing costs, however the dust covers were included in later releases.

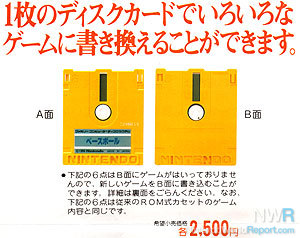

One of the big draws of disk based games was the cost. Not only were the games cheaper to manufacture on the disk-based medium, they were cheaper for the consumer as well. In the 1980s, Famicom cartridge based games usually retailed for around 5,000 yen. Brand new disk games could be purchased between 2,500 to 3,500 yen. Gamers in Japan also had a very unique option available to them that was only possible with the disk cards. Famicom Disk System owners could opt to purchase a blank disk card for 2,000 yen and then have the game of their choice placed onto the disk. They could use the disk multiple times to write different games to the disk card for the low price of 500 yen each time.

"A variety of games can be re-written on one Disk Card." (Disk Card shown: Baseball)

"A variety of games can be re-written on one Disk Card." (Disk Card shown: Baseball)The data was written to the disk cards via the Famicom Disk System Disk Writer, which was more or less a game vending machine. These machines could be found at various toy shops, department stores, and sometimes even convenience stores throughout Japan. Typically, store clerks would operate the machines for the customers.

With the advent of the disk cards, developers were not limited to the confines of the Famicom cartridges and were able to make larger games that could fit on the Disk System's larger capacity disk cards. Not only this, but at the time following up to the the release of the Disk System, players had no way to save their progress in games. The rewritable disks remedied this and allowed for more expansive gaming experiences. Some games, such as Famicom Grand Prix: F1 Race, even allowed gamers to utilize the save data on the disk to compete nationally for high scores in tournaments. Gamers could take their disks to Disk Fax Machines located throughout Japan and fax their high scores to Nintendo headquarters.

While the price and technical advancements of the disk cards were very attractive for consumers and developers, there were several issues that brought about the downfall of the Disk System. Piracy was a very big problem for the format, with pirated disk cards running rampant as well as several publications throughout Japan informing the tech savvy crowd how to copy disks. Other issues, such as reliability, were constant problems for Disk System owners. Many gamers were tormented by various disk errors relating to faulty disk cards or issues with the drive belts that would sometimes break or corrode to the point where it became unusable. From the release up until 2003, Nintendo did service faulty Disk Systems for customers. When the disk cards were working, gamers would often complain of long load times, sometimes lasting over ten seconds compared to virtually no load times with cartridge based games. By the 1990s, developers were beginning to pull away from Disk System development due to the advances made with the cartridge technology.

The Disk System was announced for release outside of Japan and although it did not utilize the expansion port on the Japanese Famicom, it is very likely that Nintendo was hoping to make use of the expansion port on the bottom of the NES. As mentioned above, the RAM adapter for the Disk System contained a special sound chip. Nintendo had originally produced the Famicom with two cartridge pins that would allow the use of external sound enhancements, in this case, enhancements coming from the RAM adapter that was plugged into the cartridge slot. In the NES, these pins were removed from the cartridge slot and positioned at the bottom expansion port, making it impossible for NES carts to make use of the sound enhancements. With this in mind, if Nintendo planned on releasing the a Disk Drive capable of connecting to the NES, it needed to be connected via the expansion port to utilize the enhanced sound capabilities. Despite all of this, the fate of the the add-on in Japan ultimately prevented it from ever seeing the light of day in North America or Europe.

The Famicom Disk System was a unique device from Nintendo and definitely taught some invaluable lessons which they took to future consoles. For instance, sticking with cartridges during the Nintendo 64 era as opposed to a CD-based medium could very well be an example of Nintendo looking back at some of the load time issues that plagued gamers back in the Famicom days. Though there were quite a few games initially released exclusively on the Disk System such as The Legend of Zelda, Metroid, and Castlevania, most of these games saw release on cartridge within and outside of Japan. Nintendo had looked into the possibility of bringing the system to North America and Europe and even went as far to more modify the internal architecture of the NES to realize this.

By the time the Famicom was nearing it's end in Japan, the Disk System unfortunately became irrelevant as cartridge based technology advanced to levels that were not thought possible during its inception. In fact, Super Mario Bros. was meant as the final cartridge game, Shigeru Miyamoto's attempt to pack in everything possible into it's 40k of space. However, two innovations, memory mapping chips, which allowed for far larger cartridge sizes, and battery-backed SRAM allowed Nintendo to return to the cartridge format, and thus ending the hope of releasing the ill-fated expansion outside of the Land of the Rising Sun.