A science lesson through the lens of pocket monsters

This requires a little bit of backstory.

Neal Ronaghan and I were brainstorming ideas for a panel to host at PAX South this year, as we were not going to do Who Wants to be a Nintendoaire (that’s being saved for PAX East). We eventually settled on submitting a 3DS Eulogy panel, which would have been similar to our previous Wii U-logy panel at PAX East a few years ago. Neal wanted to submit two panel ideas, though, to improve the chances that at least one would be picked up. From out of the left field of my brain came this: “why don’t I run a phylogenetic analysis on the first 151 Pokémon?”

You have to understand that neither one of us believed this would be picked up. The 3DS Eulogy seemed like an obvious lock. Neal submitted both ideas in late October.

On November 19th, I got the following text from Neal:

“Congratulations, your PAX South 2020 content submission “What the Heck is Mr. Mime? A New Phylogeny of Pokémon” has been accepted! We tentatively have you scheduled for Friday, January 17th at 4:00 p.m. in our Cactus Theater.”

The 3DS Eulogy panel was not accepted.

Panic immediately set in. I’d read a lot of phylogenies before—heck, being a paleontology fan exposes me to these family trees all the time—but I’d never actually written a character list, coded a data matrix, or run an analysis, which requires special software. Character lists can get pretty intense. If you want to see an actual character list by actual scientists, that employed in the description of basal paravian Hesperornithoides miessleri (check the Supplementary Information) is intimidating. I spent the next few weeks devising a character list based on Pokedex 3D Pro, an unreasonably priced application for the 3DS, which allowed me to view 3D models of every Pokémon and even see some animations which clarified a few characters (like whether they had teeth or not). My original list had over 150 characters, which I later condensed by deleting obviously apomorphic characters and getting rid of redundant characters, then I drafted a data matrix in Excel.

After that, I went on Ye Olde Internet and downloaded two freely available, widely used pieces of software used to create phylogenies: TNT and Mesquite. One again, panic set in as I realized I had no idea how to run either of these programs, and I was running out of time. In desperation, I turned to my old friend Nick Gardner, who is currently employed as a staff librarian at WVU Potomac State College in Keyser, West Virginia. The man has two lead-author publications under his belt (the braincase of Younginia and the description of new Mesozoic croc Aegisuchus). Thankfully, he was enthusiastic about this idea—teaching science through a Pokémon lens—and we immediately began collaborating on a newer, better character list. It went through five iterations in total, but once we were both reasonably happy with it, I re-coded the data matrix and Nick translated that into actual phylogenies using TNT.

Those came out in a Notebook document that did not translate well to a Powerpoint Presentation, so I drew the trees out by hand, which added another layer of DIY professionalism to the talk. The panel itself was a rousing success—we had about 300 people in the theater who were all eager to talk specifics. I was surprised and thrilled that people took to these concepts like a Seaking to water, and I got a ton of insightful questions and comments afterward. Everyone wanted to see a second version with the Gold/Silver pocket monsters included. There was a marine biologist in the crowd who suggested that many plant Pokémon are actually animals who have incorporated plants or algae into their bodies for energy. Another person suggested incorporating bird Pokémon into a real-world bird phylogeny and see who their real-world counterparts would be. One very talented tattoo artist enthusiastically offered to provide skeletals for my taxa, and showed me a Lapras skull tattoo she’d done on a friend (it’s fantastic). She lit up when I told her I’d like to (someday) do a phylogeny for Monster Hunter monsters.

The whole thing was surreal.

I’ve always believed in open science, so I’m providing two things here, for all to use and tinker with: my v.4.5 character list and my Excel data matrix. Notice that both have three parts: Nonavian Tetrapods, Avians, and Arthropods. They all use different character lists and, thus, different matrices. A future iteration of this character list can/will incorporate avian characters into the nonavian tetrapod one; there’s no reason they should be separate, since birds are tetrapods. Feathers would just be another character. Note that under these character lists, birds and bugs both came out as garbage polytomies—TNT couldn’t tell who was closer to who. That’s 150% the fault of the character list, which was compiled by yours truly.

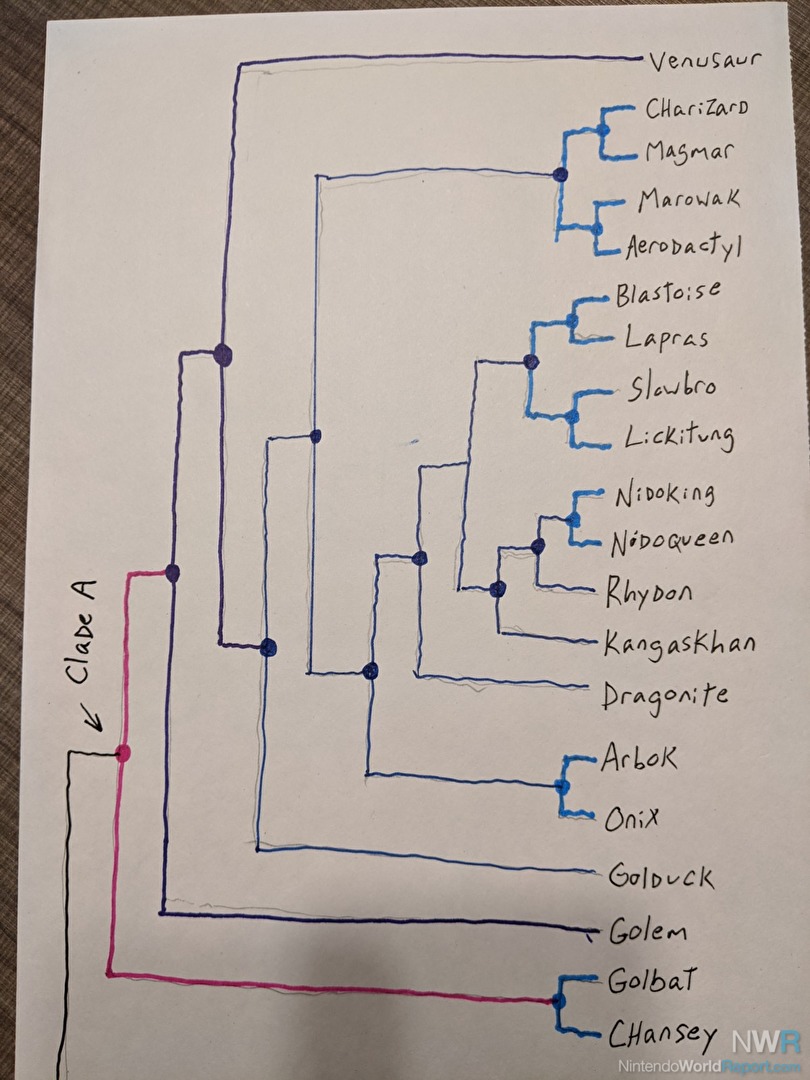

Here are some pictures of how the phylogenies turned out. The top image is the whole thing. Here is the main tree. Clade A goes off the page, as do Clades B & C. The interesting thing here is that the "human-shaped" creatures are paraphyletic--that is, they aren't strictly monophyletic. There is a monophyletic clade towards the top (no idea why Diglett is there) but for the most part, the "human-shaped" Pokémon form a stepwise progression towards Clade A, which implies that the common ancestor of Clade A was a human-shaped biped. The answer to my panel's question is here, too: Mr. Mime is, strangely enough, in a sister-group relationship with Hitmonchan. I figured it would be lower due to having five fingers but here we are. The similarities outweigh the differences. Sometimes the results are surprising, and that's a good thing.

Here's a better look at Clade A. This clade makes a lot of sense, as it includes what you might call the "dinosauroid" Pokémon. I was thrilled to see that Nidoking and Nidoqueen are sister taxa, and I'm not surprised that Rhydon and Kangaskhan are successive outgroups to that pair. They really do all look surprisingly similar. I suspect Blastoise and Lapras are together because they share a carpace but otherwise don't share that many features. Golduck was better resolved in this matrix than in the Avian matrix and forms an outgroup to the bulk of Clade A, so again, birds are dinosaurs. Although Nick suggested that it might be a sort of platypus. Not sure if it has feathers or not. Had we included Dratini and Dragonair, they would have wound up in a clade with Arbok and Onix, which is really only one branch removed from Dragonite. I don't know why Chansey and Golbat form a clade, and Golem was always going to be a total wildcard.

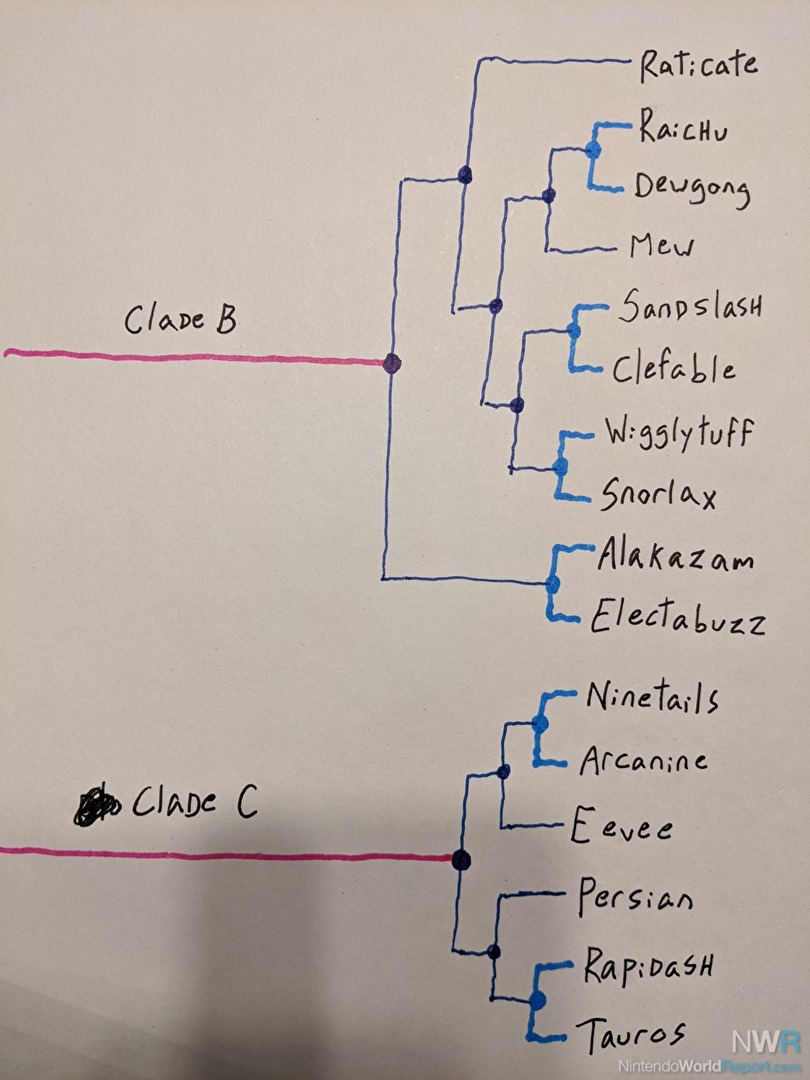

Finally, Clades B and C make a good amount of sense, too. I was surprised that Alakazam and Electabuzz didn't wind up nesting with the "human-shape" Pokémon, but instead forms an outgroup to what I'd call the "rotund bipeds." While Pokémon mythology suggests that Mew is the ur-Pokémon, it resolved better in this position. Forcing it into an ancestral position simply shifted the main branches of the tree around, but retained the core relationships, which is interesting. Seeing that all the "mammalian" Pokémon nest together in Clade C also makes me happy, although Persian forming an outgroup to hoofed mammals and not dogs is strange.

I did not include any artificial lifeforms, so no Wheezing, Magneton, Electrode, Porygon, or Mewtwo. You’ll also immediately find that I didn’t include ALL of the Pokémon, just their final evolutionary stages. I did this because, in paleontology, many studies have shown that juveniles do not wind up next to their adult forms. So, for example, if you include “Nanotyrannus” (which is a juvenile Tyrannosaurus and not a new genus) in a phylogeny, it does not come out a sister taxon to Tyrannosaurus. Several genera of duckbill and horned dinosaurs have been subsumed into established genera after people realized they were juveniles or subadults of those genera. Turns out dinosaurs changed their appearance during growth, just like Pokémon.

Had I included Dratini and Dragonair in addition to Dragonite, those first two would not be anywhere near the latter. They’d probably wind up in the same group as Arbok and Onix, as I said above, and it’s easy to see why. In fact, once you start including more taxa, they’d probably wind up next to Milotic.

However, with some finagling, I think juvenile and subadult characters can be added to the list. For example, Abra and Kadabra both have tails, but Alakazam does not, so one character could be:

Character XXX: Tail absent (0), present throughout life (1), present only in juvenile or subadult forms (3).

This would also capture Machamp, Primeape, and Poliwrath. This would sort of make sense, as these three taxa are all within a couple nodes of each other the final phylogeny.

You’ll also notice that I included Eevee as an OTU (Operational Taxonomic Unit) but didn’t include any of its evolutions. My justification for this was that Eevee represents the naturally-occurring base animal, but if that’s the case, I’d also have to leave out Raichu, Ninetails, Arcanine, Poliwrath, Clefable, Wigglytuff, Nidoking, and Nidoqueen--which I didn’t do. Besides that, somebody at the panel pointed out that Sylveon might be considered the natural adult form of Eevee, since it doesn’t require a stone to evolve. However, you could say the same about Espeon and Umbreon, so I’m not sure what to do with Eevee.

I’m leaning toward treating every single Pokémon as an individual OTU and completely ignoring the in-universe concept of “evolution.” Thus, Raichu and Pikachu would be entered separately, and we’d say they share a common ancestor, assuming they wind up near each other (no guarantee).

That would also get around things like Remoraid (a fish) “evolving” into Octillery (a mollusk). The Eevee problem would go away because we’d just assume Eevee is the basalmost taxon, a “living fossil” among the other Eevee forms. It would also get around Pokémon that can evolve into more than one form. Gloom, for example, can evolve into Vileplume or Bellossom. Now Gloom might represent an outgroup to a (Vileplume + Bellossom) clade. This would not, however, apply to Pokémon who have a “cocoon” form, like Butterfree or Tyrannitar—we would still code them as adults only. A cocoon “species” cannot exist on its own. This is one of the many ways the in-universe concept of “evolution” breaks down.

So there you have it. Go forth and make this project your own, although maybe give me a citation if you use my dataset as a base. I suspect everybody’s outcome will differ significantly. You don’t have to use Pokedex 3D Pro, of course, but your reference material should be consistent, and should incorporate as much data as you can get. The Galar Pokedex is probably the best way to currently see many Pokémon in three dimensions. I’d love it if users posted or linked to their datasets and resulting phylogenies in the Talkback below! I may well use them in my next panel.

Gold & Silver, here we come!

Also, the old Nintendo World Report Newscast crew came together at PAX South for the first time in almost ten years, and for the first time in person. Andy, Nathan, Neal - let's make this an annual thing.