Cassette tape data recording and programming on your Famicom?!

In early 1980, Hiroshi Yamauchi was looking to get his foot in the door of the expanding American video game market. By the time the Famicom had launched in the summer of 1983 in Japan, Yamauchi's son in law, Minoru Arakawa, was already hard at work opening the Nintendo of America office in the United States. Although the video game crash of 1984 all but crippled the industry, Arakawa was still intent on bringing the Famicom to the United States. Instead of marketing the unit as a toy, Nintendo intended to market the Famicom as a sophisticated electronics product, being more akin to a computer than to a video game console.

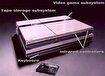

Originally called the Advanced Video System (AVS), this different take on the Famicom was going to have a slew of features that the original version of the console did not offer, such as infrared controllers, a light gun, a music keyboard, a data tape recorder, and a keyboard. The inclusion of all of these features proved to be too expensive, and while very few of them were implemented into the final design of the Nintendo Entertainment System, a handful of the aforementioned components were introduced in Japan, namely the tape recorder and keyboard, bringing interesting and unique capabilities to Famicom owners and enthusiasts.

The final design of the AVS.

The final design of the AVS.Famicom BASIC was released in Japan in 1984. Nintendo, Sharp, and Hudson collaborated on the project and made a slightly customized version of the BASIC programming language dubbed NS-HUBASIC (Nintendo/Sharp-Hudson BASIC). The package itself came with the Famicom keyboard (attaching to the Famicom via the expansion port), a special cartridge for programming in the BASIC language, and an instructional textbook to give you programming tips and answer various questions. In its lifetime, there were three releases of Famicom BASIC. Earlier models featured 1,982 bytes for executing data while the final release, the Famicom BASIC V3 in 1986, used 4,096 bytes and the SRAM that was implemented into the included cartridge to execute the data.

The Famicom BASIC V3 unit also came bundled with several mini-games featuring elements from familiar Nintendo titles. Appearances included the likes of Mario, Pauline, a crab from Mario Bros., and fireballs from Donkey Kong. The games would sometimes utilize the unique features of the Famicom, such as the built in microphone on the second controller. For example, while playing “GAME 0,” speaking into the microphone (or holding down one of the buttons) filled up an onscreen heart above Mario and Pauline. The louder you spoke, the more the heart would fill up. There was also a variety of tile sets for programming your own games. Backgrounds such as blocks, ladders, vines and girders from Mario Bros., Donkey Kong, and Donkey Kong Jr. were among the selectable items. Sprites from these games (including Pauline from Donkey Kong) were also playable and usable in your own creations.

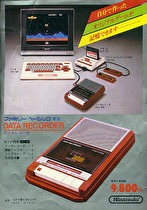

In conjunction with the Famicom BASIC set, Nintendo also released the Famicom Data Recorder. The Data Recorder, which is essentially a tape recorder that plugged into the Famicom Keyboard, allowed gamers to save various types of data on a cassette tape, including saving what you programmed with Famicom BASIC. A Nintendo branded cassette tape was included with the set, but nearly any cassette tape could be used to record data. There were a select number of early Famicom titles that utilized the Data Recorder for game saves. Excite Bike and Wrecking Crew used it for saving created tracks and levels. By the time the titles made it to outside of Japan, the save and load features included in these games could not be used. Other games that used the Data Recorder were Castlequest, Mach Rider, Load Runner, and Nuts & Milk (a Japan only puzzle/platformer from Hudson Soft).

Famicom Data Recorder

Famicom Data RecorderWhile former Nintendo of America president Minoru Arakawa originally intended that the Nintendo AVS would have both the recording device and keyboard built-in, the final version of the NES would go on to be released without them and the standalone Famicom versions never saw the light of day outside Japan.

Even early on, expansion played a huge part in Nintendo's console offerings in Japan. Although Nintendo of America ultimately decided against releasing Famicom BASIC and the Famicom Data Recorder, realizing that most American children had little to no interest in programming, these two pieces of technology show how Nintendo was attempting to find their place amongst consumers, and their market position, in the 1980s.

Photos from nesworld.com and retrogamingconsoles.com.